Strike?

April/May strikes

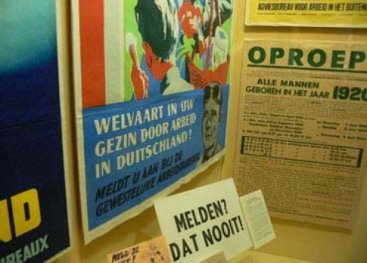

April 29th, 1943: a completely unexpected announcement was made that 300,000 Dutch soldiers would after all be transported as prisoners of war. They had been released in 1940, but now Germany needed labour forces. Spontaneous strikes broke out in the eastern region Twente and spread like lightning across large parts of the country. Femy Efftink, switchboard operator at the Stork machine factory in Hengelo, helped distribute the news about the strike: ‘At Smit Printers the rumour went round that the prisoners of war would be transported to Germany. We sent out a few messenger boys from Stork to make inquiries. After three years of occupation the time had come for us to resist. In less than half an hour the factory had emptied out. When people phoned us I asked them, “Will you go on strike with us?” And I called a number of other factories, one after another. That’s how it got started.’

The strikes later became known as the April/May strikes, or the Milk strikes, because the strikes were mainly in the countryside and in many places farmers refused to deliver milk to the dairy factories.

I was there

A housewife from Lemmer wrote in her diary: ‘That morning, strange things had happened in the area. The farmers had gone on strike – they refused to deliver the milk to the factories. So everybody went to the farms to get milk. You could have as much as you wanted. I had three two-litre canning jars full. People came lugging buckets and washtubs. There was tension in the air, because you felt this is going to lead to violence.’

Piet Stavast was a technical-school student in Pekela: ‘At the town hall work was still going on, under pressure from the NSB mayor. The strikers didn’t agree. They said they’d wait until 11 o’ clock. The mayor didn’t want a strike and threatened to call in the Germans. We just looked at the clock and waited until 11. At that moment a huge group of strikers stormed in and drove the staff out.’

Violence

Personal belongings of engineer Loep,

who was among the strikers executed.

The occupiers responded with force. Eighty strikers were executed. Their names were printed on posters as deterrence. Shots were fired on groups of strikers. An additional 95 were killed and 400 were seriously wounded. On May 3rd most of the strikers went back to work.

The strikes marked a turning point. After Amsterdam in 1941, the rest of the Netherlands had now experienced the Germany terror. Support for the resistance increased sharply. Johannes Walinga, peat cutter from Oudega says: ‘On Friday night I delivered pamphlets calling on people to strike. On Sunday morning the Grüne Polizei [German police] came. It was to be expected. Out of fear the milk factory staff gave them the names of “instigators”. ‘In that small community of ours, two men were shot and one was taken to the Dachau concentration camp. Before the strike we had never seen even one German in our village. All the dormant forces of resistance were suddenly awakened.’

A pamphlet published by the illegal newspaper Trouw stated: ‘Finally the enemy has fully stripped off his mask. The myth of the Führer’s magnanimity is at an end. Now the Germans recognize us for what we truly are: enemies, and not part of the pan-Germanic community.’

And the illegal Oranjekrant [Orange paper] wrote: ‘The limits of compliance and of passive expectation have been reached.’