Life outside the camps

Hard

Life outside the camps was hard. The economy was in poor shape. Companies came under Japanese management, Dutch banks were closed down, wages and pensions were no longer paid. Unemployment was widespread, the population became increasingly poor and hungry.

Many Dutch East Indian families moved in together or went to live with Indonesian relatives in the kampongs (native villages or areas). They were in constant fear of arrest for their anti-Japanese attitude. The Chinese did relatively well; they were indispensable for the economy because of their tradition in trade.

Work

The population was forced to work for the Japanese. Unemployed Dutch East Indian men were sent to agricultural colonies. Young Indonesian and Dutch East Indian men were taken to labour camps or deployed in paramilitary organisations.

The heihos were auxiliary soldiers for the Japanese army, and guarded the prison camps. In 1943, a real native Indonesian paramilitairy army, the Peta, was set up to assist the Japanese army.

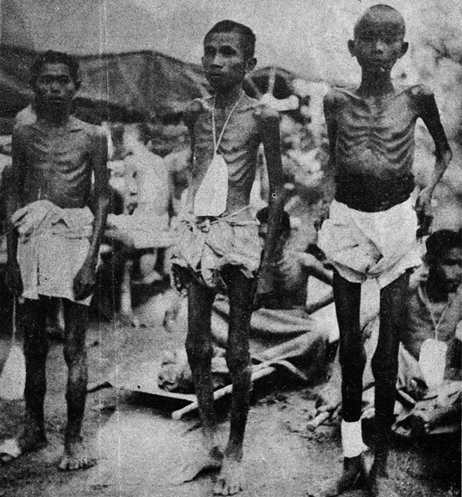

Romushas and ianfoes

Indonesians were also used as romushas (forced labourers). Tens of thousands of them died. Indonesian and East Indian Dutch girls were forced into prostitution as ianfoes (comfort girls).

Indonesians were losing their faith in the Japanese because of the harsh repression and impoverishment. Growing numbers of nationalists began to strive for independence from the Netherlands and from Japan.

Personal Stories - Survival in the kampong

Daily life outside the camps revolved around survival.

“When we lost my father’s wages, my mother rented out our house for a small sum to a Chinese person. We went to live in the kampong, close to our Indonesian relatives. When the farmers went out to harvest, we would help them. We’d collect some paddy (rice) which the women would grind. We also fished a lot. We would swap the fish for rice. If we had too little rice we would eat cassava. But if there was none of that either, we’d go hungry.”

Dutch East Indian Frans Kayatoe

Rather in a camp

The Dutch East Indian Disco family was forced to move from Makassar to the Boejoeloe enterprise inland. There, too, the conditions deteriorated: there was little food, no medical care and no education. There were anti-Dutch feelings among the native population.

Frits Disco: “My mother was so desperate at one point that she asked the Japanese whether we could be detained in a camp. At least there was some medical care there. You had to work, but at least you’d be given food. The Japanese wouldn’t send us to a camp because they did not consider us a threat.”

Native plants

The wealthy Dutch East Indian Vrijburg family sold its household goods and started growing food in the garden to survive the war.

“My father used to travel a lot before the war. He always brought back toys for us, like this beautiful pedal car. Unfortunately, it was one of the first things my mother sold to get food. Later, my mother also started to grow her own food. She used this book about native plants.”

Hilly Vrijburg

Indonesian spies

Speaking Dutch or criticising the Japanese was banned. The Dutch East Indians were afraid of betrayal.

“At one point, the Japanese ordered all older girls to work for the Japanese. My sisters Lily and Vera were the right age. They realised they would have to work in a Japanese brothel. At home they said they wouldn’t do that for anything. Indonesian spies heard this and the next day a truck with Japanese soldiers arrived. My two sisters were taken away and put in detention.”

Frans Kayatoe:

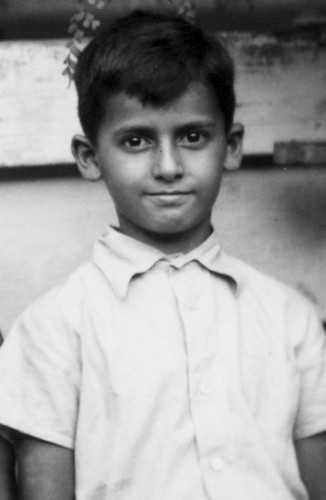

In hiding

Dutch national Jitske Brocades Zaalberg-Bergman decided not to report for detention. She went into hiding with her young son. All her friends and family were in camps. Jitske received financial support from a group of former Swiss colleagues of her husband’s, who worked for the Batavia Petroleum Company (Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij - BPM). This allowed her to smuggle food and medicine into the camp.

“Women from the camp, who had sneaked out of the camp via the sewers, would sometimes come to my house. They would order medicines or food. The Swiss helped me throughout the war. When I had appendicitis, their help got me an operation in a Chinese hospital. But I did need a pass for that. I spent an entire night forging that pass.”

Jitske Brocades Zaalberg-Bergman

Never dependent on foreigners again

Indonesian Busono was from a nationalist family. He was impressed by the strength and military aura of the Japanese. But he slowly changed his mind:

“Then we started to hear the first stories from Indonesian workers who had been sent to Burma and Thailand and the like. Stories about the terrible conditions and the many deaths. And suddenly you’d think: Listen, we have to get rid of both the Dutch and the Japanese, and we should never be dependent on foreigners again.”

Beaten with wood or rattan

In 1942, the kampong elder selected Indonesian Moentalib together with 200 others from Sampong to work for the Japanese. It was to be for three months. Moentalib eventually returned home in 1945:

“From Makassar, we were taken to Limpoeng to build an airfield. There was enough food, but we were regularly beaten with pieces of wood or rattan. I once got hit with a patjol (hoe) which made me ill for two days. Of the 200 romushas from Sampong, I saw 12 again after the war. Many died in Limpoeng.”

Hope of better times

Indonesian Moersjid volunteered for the Peta, the Indonesian army which was to fight alongside the Japanese. He believed cooperation with the Japanese would bring Indonesia’s independence closer. In 1944, he started training as an officer. He proudly posed for photographs in the bits and pieces that made up his uniform:

“For me, as a 17-year-old, it was a special moment. A new era was dawning.”

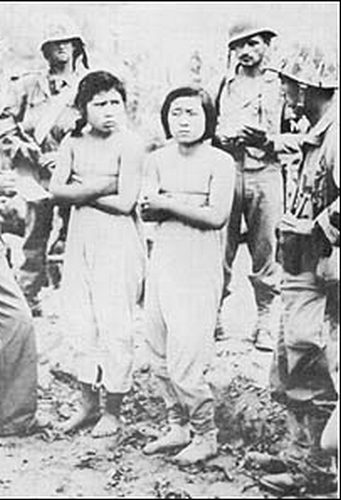

Comfort girl

Comfort girls liberated

by American soldiers.

Girls outside the camps were forced into prostitution. Sometimes, the Japanese got their ‘comfort girls’ from a camp. Ellen van der Ploeg was detained in Camp Halmaheira, together with her mother, younger sister and brother. One day, the Japanese took her and 14 other girls out of the camp:

“They promised us work outside the camp, but we were taken to an army brothel in a fancy neighbourhood of Semarang. I wore a white dress with ferns on it in the brothel. That is how I did my duty. The dress was washed every day. I constantly wanted to wash myself as well; I felt dirty. I survived by switching off. After three months we were suddenly released and returned to Halmaheira. While on the bus, I threw the little dress out of the window like a contaminated skin.”