The Japanese conquest

A worthless army

“I was by the side of the road when I saw KNIL soldiers fleeing past us. I thought: ‘What kind of soldiers are they?’ The KNIL, which always marched with such pride, turned out to be worthless. I thought it was fabulous to see how the Japanese had taken out the KNIL in a very short space of time. Even as a child I had always admired the Japanese knights, the samurai.”

Indonesian Suhendro Sosrosuwarno, age 17 when the Japanese invaded.

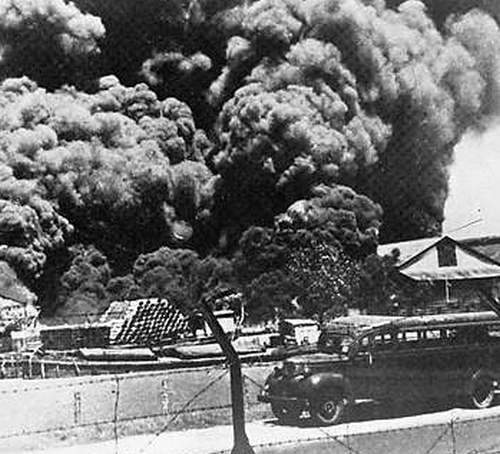

On 11 January 1942

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US naval base on Hawaii. The war had come to South-East Asia. The Dutch government in London declared war on Japan. In the East Indies, all Dutch and Dutch East Indian men between the ages of 16 and 60 were called up for military service. On 11 January 1942, Japan attacked the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch soldiers of the KNIL destroyed the main industrial plants. They were particularly keen to ensure that the oil installations would not fall into Japanese hands.

KNIL surrendered

To the great shock of the Dutch, the KNIL proved incapable of fighting the Japanese. In early March 1942, the KNIL surrendered. its troops were made prisoners of war, and the Dutch East Indies were occupied by the Japanese, ending Dutch colonial rule. Some Indonesians welcomed them as liberators. Dutch civil servants were imprisoned and their places were taken by Japanese or Indonesians.

Great East Asian Empire

The Indonesian KNIL soldiers were soon released. Japan was hoping for support from the Indonesians and the Dutch East Indians to create a ‘Great East Asian Empire’. Anyone who was not of Indonesian descent had to register. In the course of 1942, all white Dutch nationals were detained in camps. Many Dutch East Indians initially managed to stay out of the internment camps because of their Asian descent.

Personal stories - Destruction brigades

Oil company employees learned how to blow up oil and petrol stocks, so the Japanese wouldn’t be able to use them.

“I was in charge of the destruction of the oil and petrol stocks of the Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij on Borneo. The petrol had to be burned with thermite bombs hung between the barrels of petrol, with a wire leading to a battery a hundred metres away. I saw a huge flame followed by exploding barrels spewing petrol high into the sky. Thanks to the fact that the wind was blowing in the right direction, I escaped unhurt.”

Lieutenant Waasdorp, a member of a destruction brigade

In full regalia

The Japanese killed everyone who had helped in these destructions. And they held the Dutch administrators responsible for any destruction in their regions. If the civil servants remained at their posts, they were punished. On Borneo, the assistant-resident Bouwe Kuik, together with two colleagues, waited for the Japanese in full regalia. The three were stabbed to death with bayonets on the spot.

“A colleague of my father’s had said: ‘We're all going to die’, and to my father: ‘I think you should go. You have young children.’ But my father stayed. He was a devout Christian with a great sense of duty, and he had sworn an oath of loyalty to the Queen. You couldn’t just walk away.”

Daughter Ineke Kuik

The Dutch East Indies Broadcasting Company (NIROM)

Everyone listened to the radio for war news. On the day of the surrender, the Dutch East Indies Broadcasting Company (Nederlands-Indische Radio Omroep NIROM) in Batavia closed its broadcast with the words: “We are closing down now, farewell, until better days.” But the radio studio in Batavia continued to broadcast, and finished every evening with the ‘Wilhelmus’.

When, on 18 March 1942, the Japanese discovered that this was the Dutch national anthem they sprung into action. They wanted to know who was responsible for the broadcasts.

“Kusters, Kudding and Van der Hoogte said they were responsible. It all came out in separate interrogations with lots of pushing, beatings, hours of standing, and shouting, of course.” As punishment, the three were beheaded.

NIROM employee Bert Garthoff

That was a huge shock! Three men in the prime of their lives, murdered just like that.

Registration

“Obligatory registration was introduced. You had to report to the Japanese army department and state where you were born and where your parents had been born. You really had to have 85 percent Indonesian blood to stay out of the camps, but for me it was sufficient that both my parents had been born in the Dutch East Indies.”

Dutch East Indian

“We were all registered to check whether we were to be detained or not. My mother had to pay 80 guilders for her pendaftaran (registration papers), and 150 guilders for my eldest brother’s papers. But we hadn’t been paid any wages for several months. We couldn’t even buy food. My mother had to sell beautiful things to get money. I hardly ever saw my mother cry, but she cried then.”

Dutch national

“We Indonesian boys were given a Surat Ketarangan (card). It had a photograph on it to stop Dutch East Indian boys from using them. But there were Dutch East Indian boys who did have those cards. They’d forged them or been given one by the village elder, sometimes after threats or bribery.”

Indonesian

"We Chinese in the East Indies were afraid, because we knew Japan was very strong. We had heard about the atrocities the Japanese had committed in China. If you encountered Japanese people you had to bow to them, and you were beaten if you didn’t."

Chinese